Storms that battered eastern Australia and devastated seaside communities are a stark reminder of the need for a national effort to monitor the growing danger from extreme storms intensified by climate change.

“The damage we’ve seen is a harbinger of what’s to come,” said , Director of the at the University of New South Wales. “Climate change is not only raising the oceans and threatening foreshores, but making our coastlines much more vulnerable to storm damage. What are king high tides today will be the norm within decades.”

Turner’s lab manages one of the world’s longest-running beach erosion research programs, at Collaroy and Narrabeen in Sydney, using drones, real-time satellite positioning, fixed cameras, and airborne LiDAR and quadbikes. The variability, changes and trends in coastal erosion at the beaches have been tracked since 1976.

But the data collected by the UNSW team is only reliable for modelling when it comes to predicting effects in southeastern Australia. For the vast bulk of Australia’s 25,760 km long coastline, researchers – and the governments and coastal communities they advise – are largely making guesses based on limited or non-existent data, say researchers.

Climate change is not only raising the oceans and threatening foreshores, but making our coastlines much more vulnerable to storm damage. What are king high tides today will be the norm within decades.

“The wealth of data we’ve collected over decades makes our models of coastal variability increasingly more reliable – but only for a 500 km stretch of southeastern Australia,” Turner added. “But when it comes to modelling other parts of Australia, in many locations we are basically working blind.

“There are very different coasts across the country exposed to very different conditions, and we just don’t have the observational data we need to make predictions with any great confidence,” he said. “For that, we need a national approach.”

The long-term data from the UNSW program has been crucial in understanding how climate change is changing Australia’s coasts, will intensify coastal hazards, leading to changes in behaviour of storms, extreme coastal flooding and erosion in populated regions across the Pacific. As a result, estimates of coastal vulnerability – which once focussed on sea level rise – now have to factor in changing patterns of storm erosion, more intense storms, and other coastal effects.

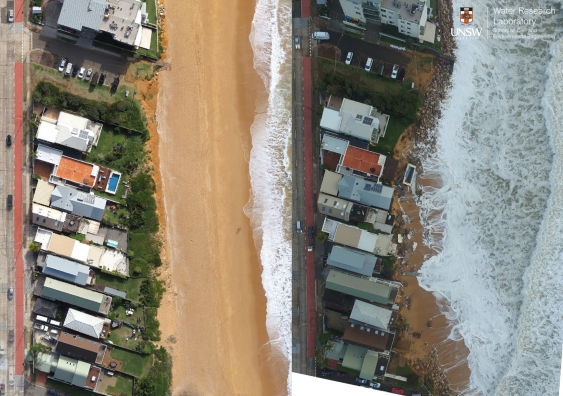

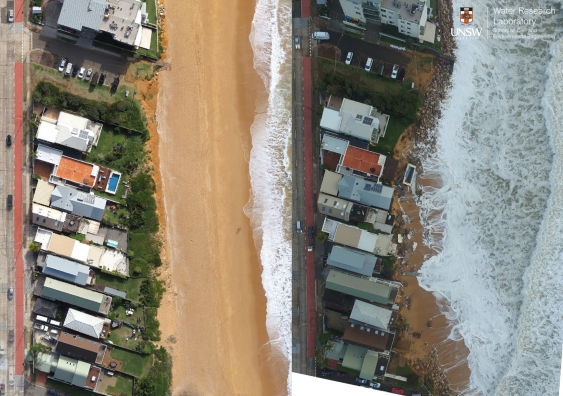

Aerial drone survey of the damaged foreshore in Sydney's Collaroy Beach. Left: 1 June 2016. Right: 7 June 2016.

Dr Mitchell Harley, a Senior Research Associate at the Lab who manages the Narrabeen-Collaroy program, said that beach erosion and coastal variability has been found to be a lot more complex than had originally thought, partly thanks to insights from the UNSW data.

“It’s now clear that sea level rise is not the only player in climate change: shifts in storm patterns and wave direction also have consequences, and distort or amplify the natural variability of coastal patterns,” Harley said.

Turner added: “These are precisely the conditions we experienced in Sydney over the past weekend – waves from the north-east, combined with unusually high sea levels brought on by king tides wreaked considerable damage. And, as sea levels rise, even ordinary tides will reach higher. What we consider king high tides today will be commonplace within decades.”

In 2014, Australian coastal researchers called for the creation of a national coastline observatory, with basic data – such as sub-aerial profiles, bathymetry and inshore wave forcing measurements – collected routinely from a network of around 20 ‘representative’ beaches across Australia. This would provide valuable data that could be used to more accurately model how Australia’s more than 11,000 beaches are changing, and predict how they will respond as climate change sets in.

The long experience gained by UNSW in Sydney’s Northern Beaches “gives us a template of what can be achieved across Australia”, said Turner. “But without consistent and national observational data – from very different regions like the tropical north, or the highly energetic southwestern coastlines, or the Indian Ocean coastlines of Western Australia – it’s of little value. To say we have blind spots is an understatement.”

Harley agreed, adding: “For the great majority of Australia’s coastlines, we don’t have observations for how they are behaving now – let alone any clear idea how they might respond to increasing variability in the future. We see it happening at Narrabeen-Collaroy, and can therefore predict it for this part of Australia. But elsewhere, we’re largely operating in the dark.”

DOWNLOADS & LINKS AVAILABLE (Please credit: “UNSW Water Research Laboratory”)

- (latest) of the Collaroy foreshore before, and after, the storm hit.

- of researchers collecting data in Sydney’s Northern Beaches.

- of the damage wrought on Sydney’s Collaroy Beach over 4-7 June.

- of UNSW drone flights (high-res) showing the extent of damage in Collaroy.

- video (latest) of Sydney’s Collaroy Beach days before, and after, the storm hit.